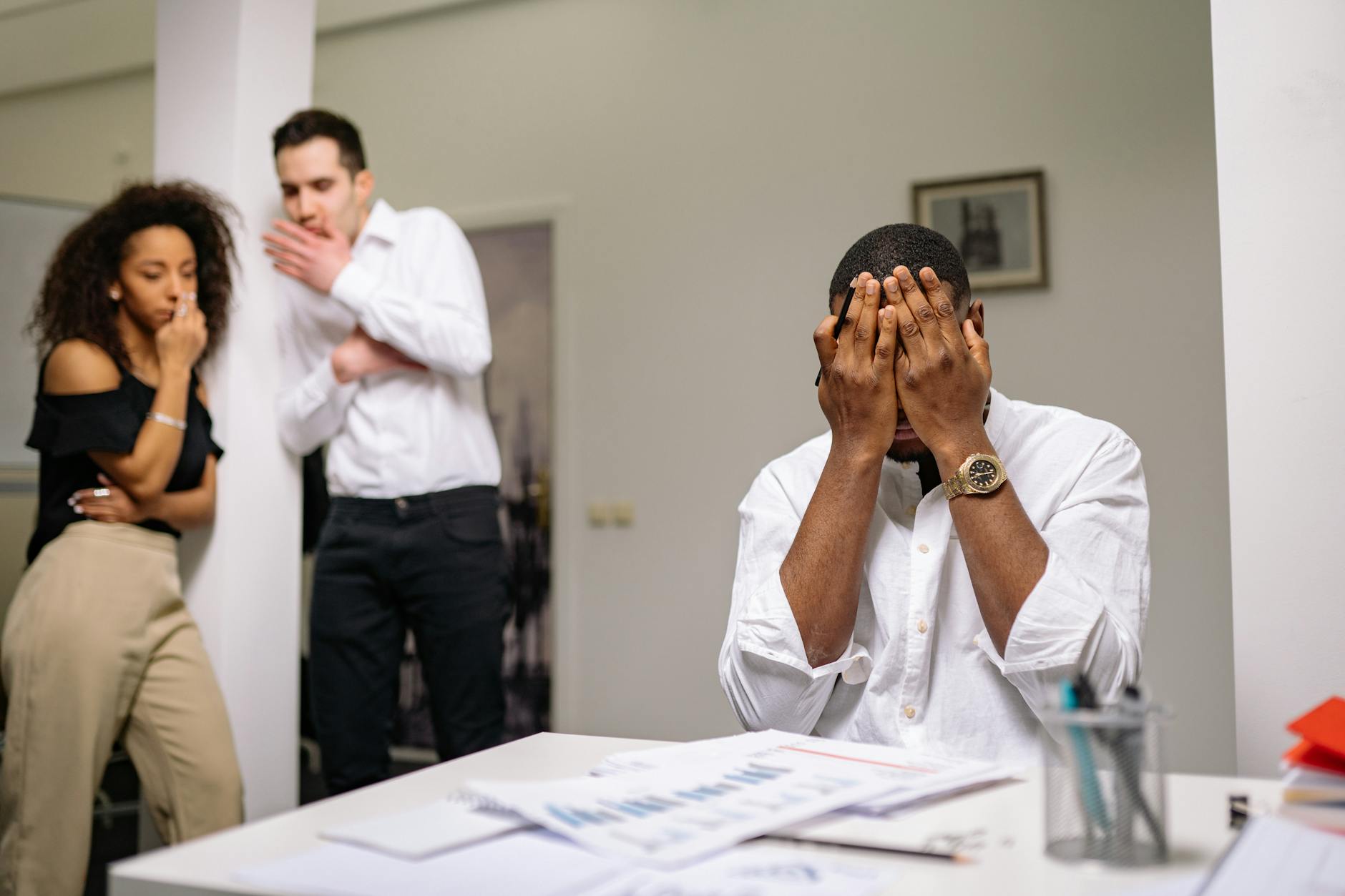

August 1, 2023, was my first official day of retirement. I left after 27 years of teaching at a small community college in western North Carolina. Officially, I retired early, but I say I ended my career right on time. Some may say that I was burned out or that I had quietly quit years before, and perhaps both are true. All I know is that I loved teaching, what it really is supposed to be, too much to keep trying to do it with little academic freedom or shared governance. I couldn’t remain in a place that cared more about enrollment and data than individual students and their learning.

Writing and editing, separate from the scads of e-mails I wrote and student writing I graded, are the things that kept me going the last few years of my teaching career. This blog, started in 2014, was the first place I regularly vented my frustrations at the negative changes I saw at my institution. But I also kept my spirits up by writing about teaching itself, some of my victories in the classroom, my memories of great teachers and wonderful teaching experiences I had.

Then, in 2017, after publishing another short story and having published dozens of theater reviews and feature articles for the local newspaper, I realized that risking rejection and criticism by putting my work out into the world not only helped me be a better writer, but it also made me a better writing teacher. I wanted to offer a special kind of professional development opportunity to other writing teachers and Teach. Write. was born. Editing Teach. Write. has been one of the joys of my life and is even better now that I have time to devote to its improvement.

However, even with the blog and the journal, the pressure was getting to me. The worst part of all was realizing how powerless I was to effect any change as I witnessed the autonomy that I had enjoyed at the beginning of my career begin to erode. So, I turned to a writing project that began as a musical but had laid dormant for several years–a satire called CAMPUS.

When it started getting particularly rough, I turned back to CAMPUS and decided, I think with the help of my wonderful daughter, that I wanted to turn my musical into a novel and keep the musical element alive by podcasting it with music. How? How would I do it? First, my daughter, a sound technician, did research on the best podcasting equipment, told my sweet husband, who bought the equipment for me as a Christmas gift. It wasn’t long before I was podcasting this crazy, satirical story about higher education at a small college in western North Carolina.

But not just any college. This enchanted campus has elves, gnomes, moon people, fairy godteachers, vampires, zombies, and a boojum–kind of an Appalachian yeti–oh, and a nazi. CAMPUS is definitely out there, but its weirdness has allowed me to say things I never could have said out loud otherwise. I produced about 13 episodes.

You can go and hear them at most podcasting platforms. Just search CAMPUS: A Novel That Wants to Be a Musical and you will find them. Don’t get too excited–the production value is low because I have no idea what I’m doing, but you know, I’m kind of proud of those episodes. I’m proud of myself for completing them, taking a chance. They helped me survive those last few years of teaching and the isolation of teaching during the worst of the pandemic years.

I want to get back to completing CAMPUS when I finish the other big writing projects on my plate right now, but until then, I will leave you with one of my favorite scenes from CAMPUS, when the discouraged, burned-out faculty makes their debut “Down at the Diploma Mill.”

DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

At that, in true musical fashion, a slow droning chant arose from across the quad as “They” began to come in. The slow heavy beat of the prison blues, the stomping of feet like the striking of a heavy hammer on a stake. THEM, teachers in ragged clothes and carrying old worn-out books came onto the quad. And they chanted:

ONCE WE WERE SOME BRIGHT YOUNG TEACHERS

ONCE WE WROTE ENGAGING LESSON PLANS

ONCE WE LOOKED INTO THEIR SHINING FACES

OUR STUDENTS WERE OUR INNOCENT LITTLE LAMBS

BUT NOW

BUT NOW

BUT NOW

CHORUS

WE’RE WORKIN’ DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

LOOKIN’ FOR SOME BRAIN CELLS TO KILL

WE NEVER MEANT IT TO BE THIS WAY

BUT WE GOT NOTHIN’ LEFT TO SAY

DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

ONCE WE HAD SOME GOOD IDEAS

ONCE WE TRIED TO CHANGE OUR WAYS

WE ALL SHUNNED STANDARDIZED TESTS

TRIED OUR BEST

TO NOT BE LIKE THE REST

BUT NOW

BUT NOW

BUT NOW

WE’RE WORKING

AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

WE’RE WORKING DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

LOOKIN’ FOR SOME BRAIN CELLS TO KILL

WE NEVER MEANT IT TO BE THIS WAY

BUT WE GOT NOTHIN’ LEFT TO SAY

DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

ASK AN ESSAY QUESTION

DO A PROJECT INSTEAD

BUT THE DEAN SAID IT WASN’T ASSESSMENT

WE SHOULD GET RETURN ON OUR INVESTMENT

IF IT’S NOT SOMETHING WE CAN CALCULATE

OR THAT’S EASY TO REGURGITATE

THEN IT’S SOMETHING YOU CAN’T DO

DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

The group begins to hum as they mount the stage and form a line of disgruntled burned out teachers. An old professor in a ragged tweed jacket with torn leather patches on the shoulder, holding a pipe comes to the mic. There is no sign of Dr. DAG. He’s gone off to Dog Hobble to that expensive restaurant only a few residents and the tourists can afford.

The old professor takes the mic as the group hums on. He speaks:

I’ll tell you what I want. Huh, come to think of it, what, exactly, do I want? I used to want to be published in exclusive journals, solicited to speak at prestigious conferences, overseas…in Europe…in Paris, all expenses paid. I wanted to be so valuable to the college I could thumb my nose at the presidents and VPs and deans and especially department chairs like Dr. C. J. Hamilton, who just had to lord over me his award-winning dissertation, the title of which he doesn’t let anyone forget– The Reawakening of Chartism and the Writings of Thomas Carlylse in the Post-Victorian/Pre-Edwardian Epoch.

Do you know what he said when I told him that I had my students all meet me at that great vegan restaurant in Asheville? He said it was stupid! Yeah. My innovative idea! A lot better than sitting around on a bunch of hard chairs in straight little rows listening to Dr. Hamilton drone on and on about Sartor Resartus and Queen Victoria’s increasing seclusion and her fat son’s sickening perversions.

My idea was great! We had a good meal, raised a few organic brews, and it was off to search for the famous O’Henry plaque embedded in the sidewalk near the cafe. We found it. I didn’t tell them that when O’Henry came to Asheville, he was a penniless drunk. How could I tell a group of 20-somethings in a creative writing class that I knew all their dreams would come to nothing?

But then we all drove together over to the Grove Park Inn to find the F. Scott Fitzgerald room. They all wanted to see the place where Fitzgerald didn’t write while he waited for Zelda to slowly lose her mind. We found the room, but I think we had all underestimated the effect of that many beers, organic or not, on our critical thinking skills. We had a hard time finding the room, and when we did and got in there… How did we get in there?

The concierge wasn’t too happy that we barged in on those German tourists. At least one of them was German because I recognized certain select vernacular. Anyway, before the burly one threw us out, I did get a glimpse around the room, a nice room, but ordinary, nothing special about it at all really. I mean why should there be? Fitzgerald just sat there, day in and day out, not writing and drinking himself into mind- numbing oblivion. On second thought, although I can’t tell you what I want, I can tell you what I don’t want. I don’t want to do this anymore.

Then the others joined him in the rousing chorus.

CHORUS

WORKIN’ DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

LOOKIN’ FOR SOME BRAIN CELLS TO KILL

WE NEVER MEANT IT TO BE THIS WAY

BUT WE GOT NOTHIN’ LEFT TO SAY

DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

The old professor sings

WHY DID I SPEND THAT MONEY TO BE A DOCTOR

WHEN ALL THEY REALLY WANT IS A PROCTOR?

WHY BOTHER CALLING ME A TEACHER

WHEN I’M JUST A FACILITATOR

FESTERING IN THIS STINKING DIPLOMA MILL?

SO, I DON’T EVEN WANT TO TRY

THE STUDENTS SAY MY CLASS IS TOO BORING

TOO MUCH GRAMMAR OR LIT STARTS THEM SNORING

I NEED TO TRY TO ASK THE GOOD QUESTIONS

NOW I CAN ONLY HIDE MY FRUSTRATION

IT’S ALL I CAN DO TO KEEP THEM FROM TEXTING

DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

And the others join in the final CHORUS

WORKIN’ DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL

LOOKIN’ FOR SOME BRAIN CELLS TO KILL

WE NEVER MEANT IT TO BE THIS WAY

BUT WE GOT NOTHIN’ LEFT TO SAY

DOWN AT THE DIPLOMA MILL